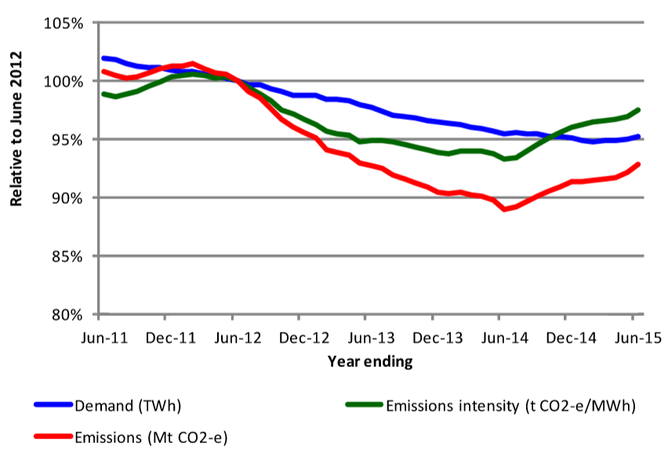

In 2012, the Australian government introduced a carbon tax on major industrial polluters on A$23 / ton. In July 2014 the Abbott government repealed it. The problem? It was actually working. Greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity sector dropped more than 10%, and emissions intensity - how much carbon you need per gigajoule - dropped by more than 5%. Both of these changes were immediately reversed on repeal:

Making polluters pay for carbon shifted generation away from lignite and towards hydro. Some of the hydro effect was short-term, driven by expectations of repeal (they mined their supplies to profit while they could); you need stable policy to affect investment decisions (alternatively, the right sort of uncertainty, creating a risk of paying rather than an expectation of not paying). Unfortunately we've made the same mistake in New Zealand, gutting the ETS and increasing pollution subsidies, leading polluters to expect they won't have to pay.

But its also worth noting that the effect of carbon pricing was rather modest (10% is good, but not enough).

Fourth, and following from the three preceding conclusions, achieving larger and faster emissions reductions will require a wide range of policies, all working in the same direction. A price on emissions, whether through an emissions trading scheme or a tax, will be a key component of such a suite, but only one component.

This is the approach being taken by all of the many countries and sub-national jurisdictions that have introduced emissions pricing.

Campaigners for the return of Australian carbon pricing shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that other policies will be needed too.

This is something we're ignoring in New Zealand too. Even if the ETS wasn't broken, we'd need more than just a market price signal to achieve the sorts of emissions reductions we need. Unfortunately, with policy still in the grip of market fundamentalists, serious policy seems unlikely.